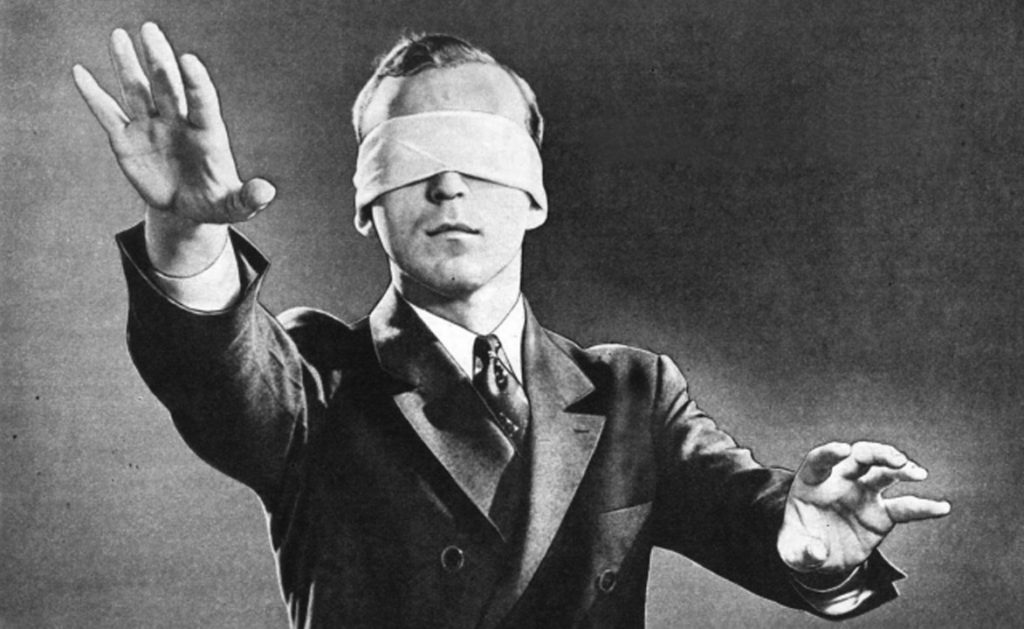

New York State’s “Blindfold Law” is legalized cheating for the DA. New York’s discovery rules allow prosecutors to withhold discovery and potentially exculpatory evidence for the defendant—evidence that could clear the defendant—until the eve of trial. This means a defendant (and his attorney) can enter trial unaware of the evidence that may be used against him by the government and without evidence that may be integral to his defense, including the simple fact of his accuser’s identity. Simply put, the defense is blindfolded.

How, you might ask, can someone defend themselves against supposed “evidence” if they don’t even know what that evidence is?

Well, for the most part, they don’t, because the prosecution uses this blindfold tactic to pressure defendants into taking guilty pleas. As reported by the New York Division of Criminal Justice Services, an astounding 98% of felony convictions are the result of plea deals. And that is not, I can assure you, because 98% of those defendants are guilty beyond a reasonable doubt (the standard of proof at trial), but instead because they feel the pressure of a system stacked against them and see no other way out than to accept a higher deal than they may deserve. Even if the government’s evidence is weak, the mere fact that they are not obligated to disclose it to the defendant means they can easily fool him into believing that what they have is stronger than it is. This “blindfold law” enables the government to intimidate vulnerable defendants into signing a plea, securing themselves a conviction that may not have resulted if the case had gone to trial.

Furthermore, when a case does go to trial, what often ensues is a trial-by-ambush. For perspective, let me tell you about a trial we had in 2015 in New York County. After months of litigation, the day before trial, the prosecutors sent over a stack of discovery documents that would rival the page count of Tolsoy’s War and Peace—not a quick one-night-ready-for-trial-read. We asked the Judge for time to review the documents—a reasonable request seeing that reviewing discovery is necessary to properly defend any client. Our request was denied, the trial proceeded, and the government presented evidence we hardly had time to review, let alone to counter. This was a trial that haunts me to this day because it is a trial we should have won. Had the government sent the discovery documents in the ample time they had to do so, we could have.

This ambush would never happen in civil court, where each side is required to comply with the standard of complete transparency. Before either side even steps foot in the civil courtroom for trial, they have each reviewed every document and piece of evidence gathered by the other side and have had the opportunity to depose every witness. A civil lawyer would never dream of settling a suit or taking it to trial without having done so. In fact, if an attorney tried to withhold discovery in civil court, both the receiving attorney and the Judge would be up in arms because it would be considered outrageous, yet this is the norm of criminal court, where the stakes—one’s fundamental rights—are incontrovertibly higher. In civil court, you may be forced to pay; in criminal court, you may go to jail and be forced to pay. My gut tells me that you would be hard pressed to find someone who wouldn’t prefer the former.

When you are forced to settle in civil court, it means you don’t think you can win at trial; when you are forced to take a plea in criminal court, you don’t have the chance to see whether you could win at trial. Even innocent people take guilty pleas when they believe the evidence is stacked against them, and it can look that way when the government is allowed to withhold evidence that might be key to a defendant’s defense. In New York and nine other states, the government can use this shady tactic to build their case and manipulate the narrative in their favor. It is abhorrent, and what’s worse is that this policy exists also at the federal level. For narrative’s sake, here’s another anecdote:

In 2014, while defending then New York City Councilman Dan Halloran who was charged as part of a conspiracy for political corruption along with New York State Senator Malcolm Smith and three others, we uncovered, through my cross-examination of FBI Special Agent William McGrogan, that the government had withheld over 9,000 wiretapped conversations between key witnesses. Their defense was that they had deemed these conversations “unimportant.” This determination, however, was not theirs to make. Judge Karas agreed and demanded that the government turn the tapes over to us immediately.

It turned out that twenty-eight hours of these conversations were in Yiddish, and since translating the Yiddish would have taken longer than the jury was available, Judge Karas was forced to order a mistrial. On one hand, a mistrial can be good for a defendant because it means the government has to start from scratch, but on the other, it means the government has to spend thousands and thousands of dollars of tax-payers’ dollars for a new trial that could have been saved had the government done what it was supposed to in the first place. Withholding evidence is neither just nor efficient, and the government should not have the power to do it.

Even without the “blindfold law,” our criminal justice system intrinsically disadvantages defendants. The government has an endless stream of resources to devote to their case. A defendant only has as much as his bank account allows. Even when someone innocent is charged, unless represented by Legal Aid, an organization whose employees are stretched very thin trying to cover an overwhelming number of cases at once, he or she will have to shell out thousands of dollars just to get their case dismissed or the charges reduced. If the case does go to trial, the cost can be crippling to the point that defendants may choose instead to take a plea—even if they are innocent.

This, paired with the fact that prosecutors can utilize the “blindfold law,” which is really just the tipping point of the rampant prosecutorial misconduct that takes place in criminal trials, makes it wholly unsurprising that conviction rates for felonies in New York are so high, around 66%, and that so many of those convictions are the result of guilty pleas. This is not what the Founders had in mind when they drafted neither the Fifth Amendment, ensuring a Constitutional right to due process, nor the Sixth Amendment right to a trial by jury.

Forty of our fifty states have reformed their laws to call for an open-discovery policy like that in civil court, having realized the antiquated restrictive discovery laws still implemented in states like New York—and at the federal level—are backwards and counter-intuitive to justice. Charles Hynes, former Brooklyn District Attorney, understood this and adopted the open-file policy years ago after a number of high profile convictions were overturned due to the suppression of evidence. Manhattan D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr. has yet to follow suit, despite New York organizational efforts to make this a state-wide policy.

In August, the New York Times published an article that highlighted efforts by organizations, including the New York State Bar Association, to raise awareness and reform this unfair, inefficient, and unethical policy, and the resistance they are facing in doing so. This month, Governor Cuomo acknowledged New York’s need for discovery reform and proposed doing away with the “blindfold law” as a provision of a larger package for criminal justice reform.

According to The Marshall Project, New York lawmakers have introduced bills for increased discovery transparency at least a dozen times in the past 25 years, yet due to powerful opposition, the bills have floundered. This opposition comes from state district attorneys who argue that a higher level of discovery transparency will endanger witnesses and lead to higher crime rates—in other words, bogus claims that are proven, by the forty states, and the Brooklyn D.A.’s office, who already have this transparency, not to be true. The assertion that implementation of this policy would increase crime is a fear mongering tactic to deny the bills public support in order to maintain the government’s unfair advantage over the defense and to preserve their high conviction rate through guilty pleas and ambushed trials.

Discovery reform in New York is imperative for a fairer criminal justice system. Our prisons are too full. Unnecessary convictions are too common. Innocent men and women are going to jail, and others are being punished longer and harsher than necessary. Leveling the playing field even slightly between the government and the defense through open-file discovery policies could lead to a significant reduction in accepted guilty pleas that should not be taken, and convictions that should not occur. Our criminal justice system is inherently supposed to be just. It isn’t even close. We must do better, and by finally following the example of the forty states with discovery transparency policies, we can take the first step.

Attorney Advertising | Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. The information on this website is for general information purposes only. Nothing on this site should be taken as legal advice for any individual case or situation. This information is not intended to create, and receipt or viewing does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.