To be an effective criminal defense counsel, an attorney must be prepared to be demanding, outrageous, irreverent, blasphemous, a rogue, a renegade, and a hated, isolated, and lonely person – few love a spokesman for the despised and the damned.

To be an effective criminal defense counsel, an attorney must be prepared to be demanding, outrageous, irreverent, blasphemous, a rogue, a renegade, and a hated, isolated, and lonely person – few love a spokesman for the despised and the damned.

These words of Clarence Darrow (1857 – 1938), America’s most famous trial lawyer, transcend time. The challenges Darrow confronted in and outside the courtroom over 100 years ago are the same for criminal defense attorneys today. Dubbed the “attorney for the damned,” Darrow represented the innocent and the depraved, the wealthy and the penniless, all the way defending each the same because he believed that every human life was worth saving. His efforts helped spare 102 defendants the death penalty. Darrow pleaded with judges and jurors that only by overcoming hate with love and by employing logic and reason instead of contempt and prejudice, could we hope to progress as a society and fulfill our human potential for greatness.

Darrow did not claim to be righteous or wise; he was aware of his own misgivings, believing he, like all men, were capable of doing both well and ill. He was agnostic, believing the fallibility of human knowledge prevented the certainty of God’s existence. That said, his firm belief in human mortality and the indivisible nature of the human spirit fueled his relentless efforts to bring civilization to a higher level and distinguished his place in American history as a formidable champion for life.

Just over a week ago, our team at Varghese & Associates had the privilege of experiencing Kevin Spacey bring Darrow’s story to life in a one-man show performed in Arthur Ashe Stadium at the US Tennis Center in Queens. For 90 minutes, Spacey breathtakingly recounted some of Darrow’s most renowned cases and delivered bits from the great speeches Darrow used to win over the hearts and minds of juries, judges, and the public.

Spacey first walked us through Darrow’s representation of Eugene V. Debs, arrested on conspiracy charges for organizing the American Railway Union strike in 1893. Darrow delivered a pointed, principled description of the restrictive, oppressive nature of the conspiracy statute that unfortunately still holds true today:

Conspiracy from the days of tyranny in England down to the day the railroads use it as a club, has been the favorite weapon of every tyrant. It is an effort to punish the crime of thought. If there are still any citizens interested in protecting human liberty, let them study the conspiracy laws of the United States which have grown until today no one’s liberty is safe…This is not the first time that evil men—men who are themselves criminals—have conspired to use the law for the purpose of bringing righteous ones to death or jail!

Darrow said Debs’ case would be an historic one, serving as a reminder that the law, simply because it is written, is not necessarily just. Darrow believed that citizens needed to fight to preserve liberty against those who would infringe upon it.

Fighting to preserve liberty is the work of a criminal defense lawyer and so is the necessity of sometimes defending those who are not righteous—but, are in fact guilty of the malicious crimes. Such was the case of Leopold and Loeb, two young, extraordinarily intelligent yet malevolent boys charged with the murder of 14-year-old Bobby Franks. They were 18 and 19 respectively at the time of the murder and known as “thrill killers.”

Loeb desired to carry out the perfect crime that would grab the entire city of Chicago’s attention—the abduction and killing of a child. Leopold worshipped both Loeb and the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche—specifically the notion of a “superman” who need not adhere to the moral code that restricts normal men. Leopold, thus, was more than happy to go along with the plan to kidnap and kill Bobby Franks.

In this case, Darrow knew, as the DA did, that the boys were guilty. They had confessed and all the evidence pointed to them. Darrow recommended they plead guilty and by doing so sought to save them from the death penalty by arguing mitigation in front of a judge instead of a jury. Darrow never tried to play down the severity of the boys’ crime, but his defense instead rested on the notion that no teenager in his right mind would lure a boy to his death simply for the thrill of it. Darrow declared that these teens were without reason.

Darrow argued to the Court:

Why did they kill little Bobby Franks? Not for money, not for spite; not for hate…Because somewhere in the infinite processes that go to the making up of the boy or the man something slipped, and those unfortunate lads sit here hated, despised, outcasts, with the community shouting for their blood…I know, Your Honor, that every atom of life in all this universe is bound up together. I know that a pebble cannot be thrown into the ocean without disturbing every drop of water in the sea. I know that every life is inextricably mixed and woven with every other life. I know that every influence, conscious and unconscious, acts and reacts on every living organism, and that no one can fix the blame. I know that all life is a series of infinite chances, which sometimes result one way and sometimes another. I have not the infinite wisdom that can fathom it, neither has any other human brain.

Leopold and Loeb were sentenced to life in prison, but escaped death at the hand of the State. Darrow is quoted to have called it “just what we asked for, but…more of a punishment than death would have been.” The work of a defense lawyer is thus—sometimes even a win is a bitter pill to swallow.

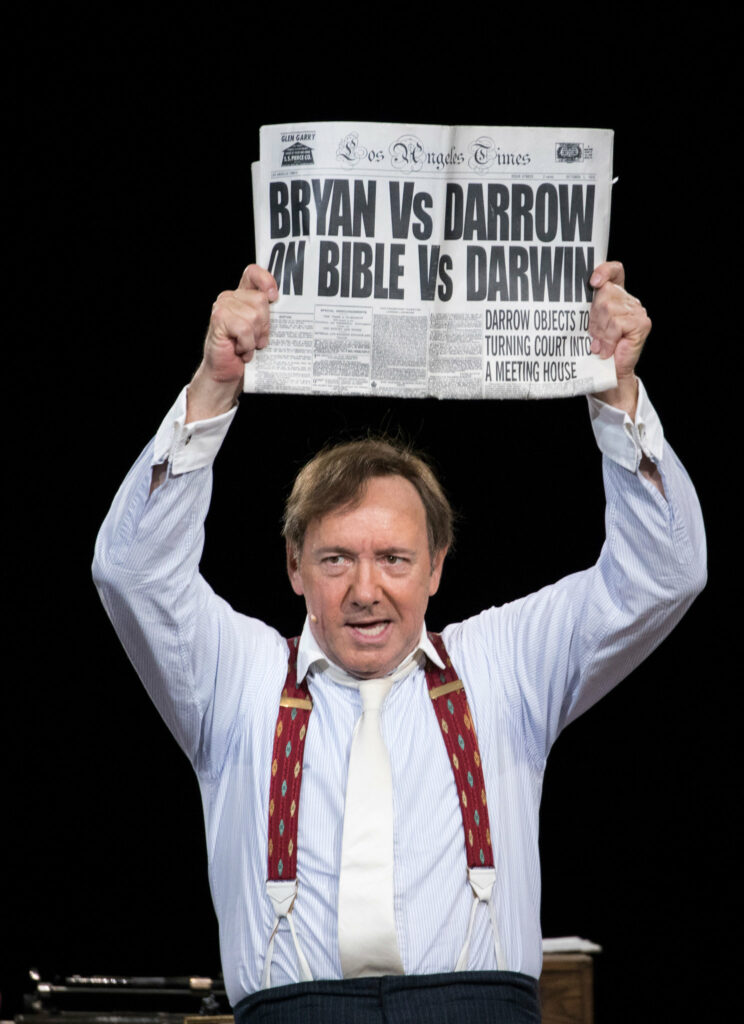

Spacey performed portions of the “Scopes Monkey Trial,” Darrow’s crusade against censorship where he warned about the slippery slope of prohibiting evolution teaching. Darrow defended John T. Scopes, charged for teaching the theory of evolution in a public school in violation of Tennessee’s Butler Act.

If today you can take a thing like evolution and make it a crime to teach it in the public school tomorrow you can make it a crime to teach it in the private schools…at the next session you may ban books and newspapers…If you can do one you can do the other. Ignorance and fanaticism is ever busy and needs feeding…After a while, your honor, it is the setting of man against man and creed against creed until with flying banners and beating drums we are marching backward to the glorious ages of the sixteenth century when bigots lighted fagots to burn the men who dared to bring any intelligence and enlightenment and culture to the human mind.

Despite losing the trial, Darrow’s logic was eventually applied by the Supreme Court when they declared that a ban such as that in Tennessee’s Butler Act violates the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. Darrow was a freethinker ahead of his time, unafraid to get under the skin of those who would seek to shield society from progress.

Darrow epitomized what the role of a criminal defense lawyer is meant to be. The age-old question posed to defense lawyers is how one can possibly defend criminals. Those who ask that question are forgetting that without a proper defense for those charged with crimes, there would be no meaning to the word “justice” in our criminal justice system.

Darrow was a voice for those who were unable to speak for themselves, those who were condemned by the public as wicked and unworthy of sympathy or compassion. He forced people to think differently and critically about human nature. At his core, Darrow wanted people to understand that no one is purely good or evil and from this understanding, comes the necessity of showing mercy to those who may not appear to deserve it.

Spacey’s last lines of the play, an excerpt from Darrow’s defense of Leopold and Loeb, encapsulates Darrow’s philosophy:

I am pleading for the future; I am pleading for a time when hatred and cruelty will not control the hearts of men. When we can learn by reason and judgment and understanding that all life is worth saving, and that mercy is the highest attribute of man.

Spacey’s tour de force performance honoring Darrow serves as a reminder, not only for those of us who practice criminal defense, but also for any citizen who finds himself or herself in a position of judgment—that we are all human. Darrow (through Spacey) showed us that we are all worthy of an equal chance, and above all, worthy of giving and receiving mercy.

Attorney Advertising | Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. The information on this website is for general information purposes only. Nothing on this site should be taken as legal advice for any individual case or situation. This information is not intended to create, and receipt or viewing does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.